Welcome, one and all, to the Tony's Reading List Awards for 2009! This is where we celebrate the previous twelve months of reading, look at what was read, where it came from and who the big favourites of 2009 were. We will also be awarding a couple of prestigious prizes: the 'Golden Turkey Award' (self-explanatory really) and the 'Book of the Year Award' (ditto).

Welcome, one and all, to the Tony's Reading List Awards for 2009! This is where we celebrate the previous twelve months of reading, look at what was read, where it came from and who the big favourites of 2009 were. We will also be awarding a couple of prestigious prizes: the 'Golden Turkey Award' (self-explanatory really) and the 'Book of the Year Award' (ditto).So, without further ado, let's begin! Firstly, the 'Most-Read Author Award' goes to Haruki Murakami:

1) Haruki Murakami (6)

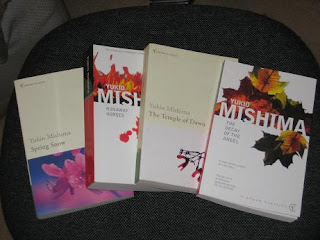

2) Yukio Mishima (5)

3=) Heinrich Böll (4)

3=) Charles Dickens (4)

3=) Thomas Hardy (4)

Belezza's Japanese Literature Challenge 3 inspired me to read more Japanese literature than I otherwise would have: the Murakami books were all rereads, but the Mishima novels (including all four 'The Sea of Fertility' works) were new to me. While Dickens and Hardy are old friends, 2009 saw German author Heinrich Böll leap into my conciousness: four down and more to come ;)

When it comes to nationality, it's no surprise that England takes out the 'Most-Read Country Award':

1) England (32)

2) Japan (15)

3) Australia (8)

4) Germany (7)

5) Russia (4)

I am (as you may know) English by birth, and I lived for three years in Japan a while back. I am now an Australian citizen, having lived here for more than seven years, and I studied German at university, later living there for two years. I have absolutely no connection with Russia whatsoever... I just checked my list, and, of the 91 books read this year, 39 were originally published in a language other than English (of which 14 were read in the original).

The 'Golden Turkey Award' goes to the book which was the biggest waste of time this year. Luckily, my prediliction for classics means that bad books have been few and far between. However, there were a few...

1) 'The Universe' by Richard Osborne

2) 'Wish You Were Here' by Mike Gayle

3) 'Blind Faith' by Ben Elton

4) 'My Favourite Wife' by Tony Parsons

5) 'Oliver Twist' by Charles Dickens

Please read my review of the awful 'The Universe' (just DON'T READ THE BOOK!). 'Persuasion' by Jane Austen managed to extract itself from the bottom five thanks to an improved performance in the second half. 'Oliver Twist' scrapes in (!) largely because of dashed expectations.

Book of the Year - Very Honourable Mentions

'The God of Small Things' by Arundhati Roy

'Die Verlorene Ehre der Katharina Blum' by Heinrich Böll

'The Trilogy of the Rat' by Haruki Murakami

'Midnight's Children' by Salman Rushdie

'Der Prozeß' by Franz Kafka

'100 Years of Solitude' by Gabriel Garcia Marquez

'Breath' by Tim Winton

'Middlemarch' by George Eliot

'Ulysses' by James Joyce

'The Riders' by Tim Winton

A bit of a cheat to include four Murakami books here, but I felt it was only fair to nominate them for the sum of their parts. Tim Winton is the only author with two separate nominations here, and I heartily recommend him to all you non-Aussies! The truth is that I had a preliminary short-list of about 25 books, and even keeping to that list caused me to cut out dozens of great books (I have had a very good reading year!).

But what gets the big award?

The 'Book of the Year Award' for 2009 goes to:

'The Sea of Fertility' Tetralogy by Yukio Mishima

No big surprise to regular readers of my blog, I suspect. Before this year, I had only read Mishima's 'The Temple of the Golden Pavillion', which I found tough going. After buying, reading and posting on 'Forbidden Colours', I decided to take the plunge and tackle all four books in Mishima's career-defining series. All I can say is that I'm very glad I did and that I think you should too!

Thanks for your time: I hope you've come away with some ideas for your reading year in 2010. Happy new Year!

.jpg)

.jpg)