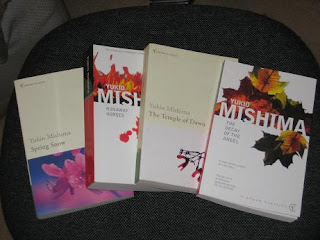

Please look to your left, dear reader (oh, alright, look to the left of this text; I don't care what you can see next to your laptop...). The lovely photo I took a few hours ago shows the complete 'The Sea of Fertility' tetralogy in all its wonderful glory (and, for some reason, in two different Vintage editions - that's the Book Depository for you). Today, about six months after finishing the first instalment, 'Spring Snow', I finally finished the fourth and final part, 'The Decay of the Angel'. Wow.

Please look to your left, dear reader (oh, alright, look to the left of this text; I don't care what you can see next to your laptop...). The lovely photo I took a few hours ago shows the complete 'The Sea of Fertility' tetralogy in all its wonderful glory (and, for some reason, in two different Vintage editions - that's the Book Depository for you). Today, about six months after finishing the first instalment, 'Spring Snow', I finally finished the fourth and final part, 'The Decay of the Angel'. Wow.As our old acquaintance Shunsuke Honda nears the end of his life, he is looking back on how he has spent it and the events concerning the three doomed young people he has been involved with. One day, while walking on a Shizuoka beach, he comes across a look-out tower and, going inside for a look around, he meets a young man named Toru Yasunaga. Naturally, Honda sees an unusual birthmark under the young man's singlet and decides to adopt him, believing him to be the next incarnation of his friend, Kiyoaki Matsugae. But is Toru all he seems?

Toru certainly seems to be special (although for all the wrong reasons); he is egocentric, self-contained, cruel and possessed of an innate sense of his own worth in the world. While Honda seeks to mould the young man, playing with him to see if he (unlike his 'predecessors') can make it to his 21st birthday, Toru has his own ideas, slowly taking over control of the household and perverting events to his own ends. Within a few years, it is unclear who exactly is controlling whom...

In previous posts, I commented on the role of the seasons in the books, but I mainly focused on the background role of the seasons against the actions of the novel. However, the idea of seasons is, of course, a metaphor for the passing of Honda's years. 'The Decay of the Angel' marks the winter of Honda's existence, and it is (as is the case for many people) a harsh winter, full of bodily and mental frailty and atrophy. The title of this instalment of the series comes from a description in Buddhist lore of the passing of an angel: five signs of decay indicate the imminent death of an angel, including increased sweating from the armpits, a sudden shabbiness of attire and an inability to motivate oneself to move from the spot. By the end of the novel, Honda is not the only character in whom these signs can be seen...

The main intrigue of the book is the question of Toru's status: is he the reincarnation of the previous characters? While some of the signs are positive, there are some doubts: both Toru's date of birth and Ying Chan's exact time of death are uncertain, leaving the possibility that Toru was born too early. In addition, while Toru is certainly different (if by different you mean evil), is he really unique? Is he such a freak of nature that he is fated to die young?

As a novel in its own right, I doubt whether 'The Decay of the Angel' would quite cut it. It is far shorter than the first three books (perhaps because Mishima had something on his mind...), and the reader does get the feeling that the story, especially the mental conflict between Toru and Honda, could have been fleshed out more. However, as the denouement of the series as a whole, it works splendidly. With the doubts thrown up about Toru's status, Honda's whole existence is put under the microscope. Why has he spent so much of his life obsessing over Kiyoaki and his successors? Why has he become the cold, voyeuristic, secluded old man we see in this book?

The end gives us some of these answers but creates a whole host of others; on a visit to the Nara temple where Satoko, Kiyoaki's lover, shut herself away from the world, the dying Honda recreates Kiyoaki's painful pilgrimage of sixty years ago to obtain an audience with the abbess in an attempt to obtain some kind of truth or justification for all that has gone before. What actually confronts him... Well, you'll just have to read the book for yourself.

So what is it all about? Not a clue, but, in the countless rereadings this series will attract over the coming decades, I hope to get a glimpse of the ideas Mishima wove into his four-novel canvas. Reincarnation, the inevitable decay of earthly flesh (and society...), the recreation of the universe after every breath, every second, the nature of destiny, the lot of the unnatural or superhuman, the impossibility of sustaining perfect beauty in a less-than-perfect world... It cannot be described: it must be read.

Please do so.