*****

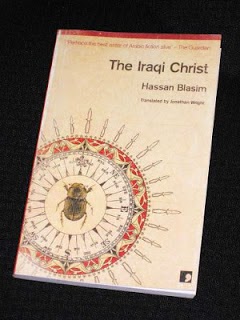

If I'm being honest, it's not a result I would have predicted, but I am very happy for the publisher, Comma Press, for the publicity and praise they're getting for their work in translating shorter fiction into English. Boyd Tonkin, the chair of the IFFP panel, showed a couple of years back that he has a soft spot for the press with his infamous 'double suicide' quote (claiming that with translated fiction and short stories both a hard sell, doing both together was a rather foolhardy endeavour...). I've reviewed several of their books, and I'd heartily recommend collections like Gyrðir Elíasson's Stone Tree and the collection of Chinese contemporary fiction, Shi Cheng (Ten Cities). Oh, and Blasim's book, of course ;)

In addition to the awarding of the main prize, the organisers also saw fit to laud another of my favourite presses. Birgit Vanderbeke's The Mussel Feast, translated by Jamie Bulloch, was singled out for special praise, and I'm sure I wasn't the only one thrilled to hear Peirene Press' name mentioned on the night, even if it wasn't quite the mention they were hoping for. Well done to Meike and the team (including the flighty Nymph...) - sadly, though, the first female winner is at least another year away...

*****

Of course, we in the Shadow Panel published our winner the day before the official announcement, our pick being Jón Kalman Stefánsson's The Sorrow of Angels (translated by Philip Roughton, MacLehose Press). The fact that our favourite wasn't even shortlisted for the official prize shows how important it is to have someone keeping tabs on the professionals - you can't always trust them to choose the best books ;)

A while back I expounded on this a little in my post on the differences between the IFFP and the American version, the Best Translated Book Award. While the BTBA has its own issues (as the amount of fiction available in translation increases, its anyone-can-enter ethos is bound to come under pressure), I do feel that the American version is slightly more daring than the IFFP, with the writing prized more highly than any political concerns.

A while back I expounded on this a little in my post on the differences between the IFFP and the American version, the Best Translated Book Award. While the BTBA has its own issues (as the amount of fiction available in translation increases, its anyone-can-enter ethos is bound to come under pressure), I do feel that the American version is slightly more daring than the IFFP, with the writing prized more highly than any political concerns.Sadly, I can't pretend that that's true over in the UK. It's an important event for translated fiction, but I can't help scratching my head at times over some of the decisions they come up with. It's often hard not to feel that there's a bit of an agenda there, meaning that some great books miss out while others (better fitting certain categories) seem to sneak in instead. Still, let's try to move on with grace - here's looking ahead to 2015 ;)

Before we leave 2014 behind though, there's one more aspect of the prize I need to discuss, and that's the work of the Shadow Panel. Stu and I were back for our third go this year, but the other four members, Tony, David, Jacqui and Bellezza, were tackling the task for the first time. Thanks to their efforts, this was easily the most successful and professional effort so far, with more opinions and reviews helping to balance out the views (in the past, Stu and I have had a disproportionate influence on some of the decisions). Thanks again to everyone for all the hard work over the past three months - let's hope everyone is able to go through it all again next year :)