Welcome to German Literature Month, thirty days showcasing the best fiction, modern and classic, written in the German language :) It's very important to note that the month is about celebrating the language, not the country - throughout the month, I'll be trying my best to mix it up when it comes to geography, chronology and genre.

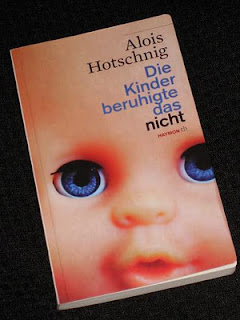

To start off then, it's only fitting that I branch out a little from my usual classic German novels and novellas and introduce a collection of short stories from a contemporary Austrian writer (one which many of you may have heard of...). Alois Hotschnig's slender collection of stories, Die Kinder beruhigte das nicht, also known by the English title of its Peirene Press translation, Maybe This Time, comprises nine tales, all of which are normal enough on the surface, but which eventually become... well, ever so slightly creepy.

The first story, Dieselbe Stille, dasselbe Geschrei, is a good example of what the collection is about. A man who has recently arrived in his area tells us about his neighbours, a couple who spend all day lounging around on a deck by the river at the back of their house. This seemingly innocuous behaviour gradually makes the man feel strangely oppressed, and his waking (and sleeping) moments begin to be filled with his obsession over the neighbours' lack of activity. Very quickly though, despite the sympathetic first-person narrative, the reader starts to mistrust our guide - especially when he starts using binoculars to spy on the couple...

Hotschnig elegantly plays with the idea of a man unable to move on with his life, caught up obsessing on something he doesn't understand, and it's a theme which crops up several times in the collection. In Vielleicht diesmal, vielleicht jetzt (the story which gives the English translation its name), it's a whole family which is unable to live their lives, waiting as they are for the mysterious, ever-elusive - and ever-absent - Uncle Walter to join them at a family gathering. In Morgens, mittags, abends (probably my favourite of the nine stories), a whole area seems to be caught in a loop, people watching people, crossing roads, walking down the street and coming back again, all fixed in time by an event we are unaware of until the last paragraph. One aspect of this story I loved was a girl playing the flute, practicing the same few bars over and over again, breaking off at the same point each time - very much like a stuck record.

Hotschnig elegantly plays with the idea of a man unable to move on with his life, caught up obsessing on something he doesn't understand, and it's a theme which crops up several times in the collection. In Vielleicht diesmal, vielleicht jetzt (the story which gives the English translation its name), it's a whole family which is unable to live their lives, waiting as they are for the mysterious, ever-elusive - and ever-absent - Uncle Walter to join them at a family gathering. In Morgens, mittags, abends (probably my favourite of the nine stories), a whole area seems to be caught in a loop, people watching people, crossing roads, walking down the street and coming back again, all fixed in time by an event we are unaware of until the last paragraph. One aspect of this story I loved was a girl playing the flute, practicing the same few bars over and over again, breaking off at the same point each time - very much like a stuck record.

To start off then, it's only fitting that I branch out a little from my usual classic German novels and novellas and introduce a collection of short stories from a contemporary Austrian writer (one which many of you may have heard of...). Alois Hotschnig's slender collection of stories, Die Kinder beruhigte das nicht, also known by the English title of its Peirene Press translation, Maybe This Time, comprises nine tales, all of which are normal enough on the surface, but which eventually become... well, ever so slightly creepy.

The first story, Dieselbe Stille, dasselbe Geschrei, is a good example of what the collection is about. A man who has recently arrived in his area tells us about his neighbours, a couple who spend all day lounging around on a deck by the river at the back of their house. This seemingly innocuous behaviour gradually makes the man feel strangely oppressed, and his waking (and sleeping) moments begin to be filled with his obsession over the neighbours' lack of activity. Very quickly though, despite the sympathetic first-person narrative, the reader starts to mistrust our guide - especially when he starts using binoculars to spy on the couple...

Hotschnig elegantly plays with the idea of a man unable to move on with his life, caught up obsessing on something he doesn't understand, and it's a theme which crops up several times in the collection. In Vielleicht diesmal, vielleicht jetzt (the story which gives the English translation its name), it's a whole family which is unable to live their lives, waiting as they are for the mysterious, ever-elusive - and ever-absent - Uncle Walter to join them at a family gathering. In Morgens, mittags, abends (probably my favourite of the nine stories), a whole area seems to be caught in a loop, people watching people, crossing roads, walking down the street and coming back again, all fixed in time by an event we are unaware of until the last paragraph. One aspect of this story I loved was a girl playing the flute, practicing the same few bars over and over again, breaking off at the same point each time - very much like a stuck record.

Hotschnig elegantly plays with the idea of a man unable to move on with his life, caught up obsessing on something he doesn't understand, and it's a theme which crops up several times in the collection. In Vielleicht diesmal, vielleicht jetzt (the story which gives the English translation its name), it's a whole family which is unable to live their lives, waiting as they are for the mysterious, ever-elusive - and ever-absent - Uncle Walter to join them at a family gathering. In Morgens, mittags, abends (probably my favourite of the nine stories), a whole area seems to be caught in a loop, people watching people, crossing roads, walking down the street and coming back again, all fixed in time by an event we are unaware of until the last paragraph. One aspect of this story I loved was a girl playing the flute, practicing the same few bars over and over again, breaking off at the same point each time - very much like a stuck record.

Another idea the writer explores is the idea of watching, and the majority of the stories (if not all of them) contain the verb beobachten, to watch or observe. In Zwei Arten zu gehen, a woman walks down the street, shadowed by a man who could be either a stalker or a former lover (we're never completely sure which...); Eine Tür geht dann auf und fällt zu, one of the creepiest of the tales, has its hero in a sort of trancelike state, observing himself at various times in the past, while being watched by a rather strange old lady (with a penchant for dolls...); In meinem Zimmer brennt Licht, a story about a man with a hidden past, is full of people observing each other, looking for hints of what might be hidden behind silence.

Most of these observers appear to be watching other people, not because the observees are doing anything wrong, but because the observers are living their lives through other people, needing other people's approval. This idea is taken to extremes in Du kennst sie nicht, es sind Fremde, a story in which a man's identity constantly changes - an issue nobody has a problem with except the man himself. One way of interpreting this story is that we are what other people see us as and that our identity is externally created (although this little tale takes the idea further than one would expect!).

The ideas in the stories are excellent, and they are all wonderfully constructed. I went through the collection for a second time a week after the first reading, and if anything, I enjoyed it more the second time around (a sure sign of a good piece of writing).

However, the success of the book is not limited to the ideas as the writing style is also key to the way the stories unfold. The majority are told in the first person, unravelling in a near-constant interior monologue mostly uninterrupted by any dialogue (what little conversation there is is reported), and the sense of things being slightly off-kilter is heightened by the frequent use of contradiction within sentences, the narrator backtracking on an idea within seconds. If the storyteller isn't completely sure of what they are saying, then how on earth can we trust them...

There are a lot more things I'd love to say about Die Kinder beruhigte das nicht, and considering that the book comes in at a mere 120 pages, that probably gives you as much of an idea of how highly I rate this slender tome as a few more paragraphs would ;) It has been described as Kafkaesque, and I can only agree with that assessment. While there's little here that could be described as extraordinary or supernatural, you can't help but get the feeling that it's all just a little bit... wrong. But, in another sense, it's very right :)